Disclaimer: The Blog on ‘Financial Shenanigans’ is not a recommendation to buy / hold / sell any stock. The published post is for information purpose only. Please read the detailed disclaimer at the bottom of the post.

Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance Or Economic Health By Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 2

Below article is follow up of the article – “Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance Or Economic Health By Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 1”. You can read the first part of the article here – Link

Investors rely on the information that they receive from corporate executives to make informed and rational securities selection decisions. This information is assumed to be accurate, whether the news is good or bad. While most corporate executives respect investors and their needs, some dishonest ones hurt investors by misrepresenting the actual company performance and manipulating the company’s declared earnings. Part 2 fleshes out the Earnings Manipulation (EM) Shenanigans which inflate current period earnings and suggests how skeptical investors can ferret out these tricks to avoid losses.

Earnings Manipulation tricks can be categorised into two major subgroups: Inflating current-period earnings and Inflating future-period earnings

Inflating Current Period Earnings:

In order to inflate current-period earnings, management must either push more revenue or gains into the current period or shift expenses to a later one. Below shenanigans can be categorised in this subgroup:

EM 1 – Recording Revenue Too Soon

EM2 – Recording Bogus Revenue

EM 3 – Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities

EM 4 – Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period

EM 5 – Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses

Inflating Future Period Earnings (Discussed in next part):

To inflate tomorrow’s operations, management would simply hold back today’s revenue or gains and accelerate tomorrow’s expenses or losses into the current period. Now you might be thinking why would a company want to report smaller profits? Consider a company that is growing like gangbusters and is unsure of what tomorrow holds, or one that has benefited from a large windfall gain or a huge new contract. Investors surely would love to see those delicious numbers, but they also would naturally expect management to duplicate or even exceed them tomorrow. Meeting those unrealistically high investor expectations may be virtually impossible, leading management to feel compelled to use this technique. Below shenanigans can be categorised in this subgroup:

EM 6 – Shifting Current Income to a Later Period

EM 7 – Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

Lets now look at these earnings shenanigans one by one:

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 1: Recording Revenues Too Soon:

1. Recording Revenue Before Completing Any Obligations under the Contract:

Executives at Computer Associates regularly stretched out the last month of the quarter to as much as 35 days and both backdated and forged sales contracts to trick their auditor and their investors into believing the company’s fictitious sales growth.

What may have led management to embark with such great zeal on pushing sales and Computer Associates’ stock price higher and higher? As per the terms of the company’s 1995 Key Employee Stock Ownership Plan (KESOP), which would reward Computer Associates’ top three executives with millions of additional shares if the share price reached certain levels and remained above those levels for at least 30 consecutive days. After a certain amount of time (and a certain number of stock splits), more than 20 million shares were actually issued. Then finally it happened—drum roll, please! On one not-so-ordinary day in 1998, they hit the $1.1 billion jackpot when the company’s share price closed at just over $55, with Chief Executive Officer Charles Wang receiving 12.15 million shares, Chief Operating Officer Sanjay Kumar 6.075 million, and Executive Vice President Russell Artzt 2.025 million (worth $669.8, $334.9, and $111.6 million, respectively).

2. Recording Revenue Far in Excess of Work Completed on the Contract:

Next, we discuss revenue recognition in situations in which the seller has started to deliver on the contract. Our friends at Computer Associates sold long-term licenses allowing customers to use its mainframe computer software. Customers paid an upfront licensing fee for the software, as well as an annual charge to renew the license in subsequent years. Despite the long-term nature of these agreements (some contracts lasted as long as seven years), the company would recognize the present value of all licensing revenue for the entire contract immediately. Since all licensing revenue was recorded at the beginning of the contract, and cash was not collected for many years to come, Computer Associates recorded large amounts of long-term receivables on its Balance Sheet.

The SEC charged that from at least January 1998 through October 2000, Computer Associates prematurely recognized over $3.3 billion in revenue from at least 363 software contracts with customers. Computer Associates’ bulging long-term receivables should have alerted investors to the company’s aggressive revenue recognition. Investors should use a measure called days’ sales outstanding (DSO) to evaluate whether customers are paying their bills on time. With the company’s long-term installment receivables soaring at September 1998, its DSO reached an unsettling 247 days (based on product revenue)—a year-over-year increase of 20 days. Furthermore, total receivables, including both current and long-term, increased to 342 days—a jump of 31 days.

Also, booking access revenue will never convert into cash leading cash flow from operations to materially lag behind net income.

Certain types of long-term contracts, however, actually allow the seller to recognize some revenue even though future services remain to be provided. Contracts like – (1) long-term construction contracts that use percentage-of-completion accounting, (2) lease agreements, (3) arrangements with several distinct deliverable s, and (4) Utility contracts recorded using mark-to-market accounting.

The revenue recognized under above contracts are subject to various estimates, and as a result, this accounting methodology creates opportunities for financial shenanigans. Investor should dig deeper and question managements on these kinds of contracts.

3. Recording Revenue Before the Buyer’s Final Acceptance of the Product:

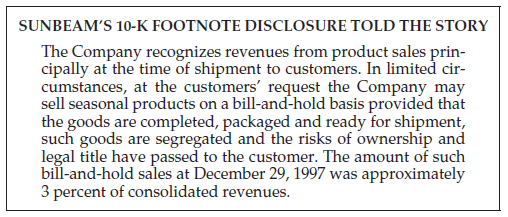

One problematic and often controversial method of revenue recognition involves so-called bill-and-hold arrangements. Under this approach, the seller bills the customer and recognizes revenue, but continues to hold the product. For most sales, with a few exceptions discussed in the prior section, revenue recognition requires shipment of product to the customer. Accounting guidelines allow revenue to be recognized in bill-and-hold transactions, however, provided that the customer requests this arrangement and is the main beneficiary.

However, Sunbeam CEO Al Dunlap used a bill-and-hold strategy in order to make the company’s financial performance appear better than it really was by artificially inflating Sunbeam’s revenue. Sunbeam, anxious to boost sales in its “turnaround year,” hoped to convince retailers to buy grills nearly six months before they were needed. In exchange for major discounts, retailers agreed to purchase merchandise that they would not physically receive until months later and would not pay for until six months after billing. In the meantime, the goods would be shipped out of the grill factory in Missouri to third-party warehouses leased by Sunbeam, where they would be held until the customers requested them.

Part of Krispy Kreme’s revenue comes from selling doughnut making equipment to its franchisees. It certainly would be appropriate for the company to record sales revenue upon shipment of a machine to a franchisee—provided, of course, that the machine was actually received by the franchisee. In 2003, Krispy Kreme went to great lengths to fool its auditors by pretending to ship equipment to franchisees. It actually shipped the equipment out, but to company-owned trailers to which the franchisees had no access. Krispy Kreme still recorded the revenue, even though the franchisees had failed to take possession of the machines shipped.

Another trick includes recording revenue by delivering wrong product to the customer. Sometimes companies scheme to inflate revenue by intentionally shipping out the wrong product and recording the related revenue, although they know full well that the product will be returned. Not surprisingly, our friends at Symbol Technologies allegedly shipped incorrect product without customer approval. Similarly, at the end of the fourth quarter of 1996, Informix recorded a sale but failed to deliver the required software code prior to year end. Then, in January 1997, Informix delivered a beta version of the software code that did not function with the hardware. It took the company another six months to deliver usable software code. As a result, Informix recorded revenue in the fourth quarter of 1996 rather than the third quarter of 1997.

4. Recording Revenue When the Buyer’s Payment Remains Uncertain or Unnecessary:

At computer systems maker Kendall Square Research Corporation, all of that took place—the product was shipped, and the customer accepted it. The final question was whether the customer had the wherewithal and the intention to pay. Many of Kendall Square’s customers—mainly universities and research institutions— required a third party to provide the funds. In reality, the sale was contingent on the receipt of outside funding, and no revenue should have been recognized until such funding had been secured. In addition, Kendall Square provided customers with “side letter” agreements that essentially voided the sale if they failed to receive funding.

A shareholder lawsuit charged that nearly half of Kendall Square’s reported revenue in the first quarter of 1993 had been improperly booked. Most of this revenue came from shipments to the University of Colorado and the Applied Computer Systems Institute of Massachusetts before these customers had received the required funding. The company eventually restated its financial statements for fiscal 1992 and the first half of 1993, reversing approximately half of its previously reported revenue.

When management employs Shenanigan No. 1, it clearly has concluded that the current period takes precedence over a later one, as it is depleting revenue from the later period and adding it to an earlier one. Had management properly posted a credit to the reserve account with services still to be provided, that credit reserve would be released as revenue in future periods.

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 2: Recording Bogus Revenue:

1. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack Economic Substance

The first technique involves simply dreaming up a scheme that has the “look and feel” of a legitimate sale, yet in reality lacks economic substance. In these transactions, the so-called customer is under no obligation to keep or pay for the product, or nothing of substance really was transferred in the first place.

Industry leader AIG’s, September 2000 earnings release did not go well. Many analysts were unsettled by an unexpected decline in AIG’s insurance liability reserve. They were asking questions about this decline, and some worried that AIG had released reserves to make its numbers for the quarter.

To help solve its Wall Street problem and boost the troubling anemic reserve balance, AIG sought the assistance of Gen Re to structure a sham reinsurance arrangement. Since AIG was one of Gen Re’s largest clients, Gen Re acquiesced and actively participated in the fraud, for which it would later pay dearly.

Here’s how it went down. AIG received $500 million in purported insurance premiums from Gen Re, which it used to beef up its loss reserves. At the same time, AIG paid $500 million to Gen Re to reinsure a risk which It used the transaction to inappropriately prop up its loss reserves. In its sham arrangement with Gen Re, AIG could just as easily have decided to record bogus revenue instead of propping up its reserves. However, AIG’s goal was to increase its reserve account, not to inflate revenue—at least not yet. If a reserve is bogus and no future payment exists, a company can easily make a bookkeeping entry that releases the reserve to report phony income.

So, AIG actually improperly benefited twice from this shenanigan. First, when it created a bogus liability reserve, Wall Street analysts were mollified by the high reserve balance. Then, with the “reloaded” reserve, AIG gave itself an opportunity to “flip the switch” and release these reserves into income. The plan worked great for a while—or until the regulators started sniffing around.

In May 2005, AIG announced a staggering $2.7 billion restatement, correcting misstatements for the previous five years. The following February, AIG paid another $1.6 billion to settle litigation as part of a global resolution of federal and state actions.

Not surprisingly, creating bogus revenue from transactions that lack any economic substance extends far beyond insurance companies. Our friends at Symbol would do virtually anything, including losing money, just to recognize a sale. In a bizarre story, Symbol concocted a three-party circular scam to create fake revenue out of thin air. Typically, Symbol sold its product to a middleman (a distributor), who then sold the product to the actual customer (the reseller). Symbol found a way to use this structure to create bogus revenue: it improperly enticed (really, bribed) the reseller to purchase more of Symbol’s product from the distributor. The distributor would, in turn, purchase more products from Symbol. What a way to create artificial demand!

How did Symbol entice its resellers to go along with this scheme? Well, Symbol allegedly gave the resellers the cash they needed to make these purchases. Symbol also paid a substantial markup so that the resellers could turn a profit on these transactions. On top of that, Symbol paid resellers a bonus equal to 1% of the purchase price (referred to by the Symbol schemers as “candy”). The net result of this transaction was that Symbol purchased its own product back at a much higher price than that at which it had initially sold it. Symbol did not mind the loss, however, as the scheme was all in the name of revenue growth. In this bizarre scheme, Symbol actually lost millions of dollars on this circular sham transaction. The scheme produced the desired revenue, but Symbol suffered losses by effectively buying back its own products at a higher price and paying what amounted to a bribe.

2. Recording Revenue from Transactions That Lack a Reasonable Arm’s-Length Process

Transactions that lack a reasonable arm’s-length process are sometimes appropriate. But prudent investors should bet against it. That is, most related-party transactions that lack an arm’s-length exchange produce inflated, and often phony, revenue.

A representative case in point is the alleged fraud at Syntax- Brillian Corp., the Arizona-based maker of high-definition televisions. Extraordinary demand in China sent sales of TVs soaring, and a new marketing relationship with ESPN and ABC Sports generated a buzz about its Olevia HDTVs. The company more than tripled its revenue in fiscal 2007, with sales approaching $700 million, up from less than $200 million the prior year. Yet one year later, Syntax-Brillian was bankrupt and under investigation for fraud.

The company’s staggering revenue growth came from a tenfold increase in sales to a related party that accounted for nearly half of its total revenue—an Asian distributor named South China House of Technology (SCHOT). The two companies seemed to be involved in a tangled web of joint ventures (which also, oddly, included Syntax-Brillian’s primary supplier). Syntax-Brillian was close enough with SCHOT that it granted it 120-day payment terms and routinely extended those terms even further.

Syntax-Brillian described SCHOT as a distributor that would purchase its TVs and then resell them to retail outlets and end users in China. Many investors failed to question the company’s significant uptick in sales to SCHOT, as they believed that demand in China was high, with people upgrading their TV sets heading into the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

Then all of a sudden, in February 2008, Syntax-Brillian cryptically announced that the Olympic facilities would no longer be installing the TVs that the company had “sold” to South China House of Technology. Even though Syntax-Brillian had already recorded revenue from the sale of these TVs, it agreed to “repurchase” more than 25,000 TVs for nearly $100 million. The company did not need to come up with the cash because the receivable from SCHOT was, of course, still outstanding. With this significant right of return and no receipt of cash, Syntax-Brillian should never have recognized this revenue in the first place! Syntax-Brillian’s elaborate related-party transactions (and many other red flags, such as surging receivables) were in plain sight for any investor who read the SEC filings.

3. Recording Revenue on Receipt from Non-Revenue Producing Transactions

Investors understand that not all cash received represents revenue or even directly pertains to a company’s core operations. Some inflows are related to financing activities (borrowing and stock issuance), and others to the sale of businesses or sundry assets. Companies that recognize revenue or income from non-revenue producing sources should be deemed guilty of reporting phony revenue to inflate earnings.

Apparently, auto parts manufacturer Delphi Corporation failed to understand the distinction between a liability and revenue. In late December 2000, Delphi took out a $200 million short-term loan, posting inventory as collateral. Rather than recording the cash received as what it was (a liability that needed to be paid back), Delphi improperly recorded it as the sale of goods. This twisted interpretation not only allowed Delphi to record bogus revenue, it also provided bogus cash flow from operations.

Generally, cash flows with vendors involve cash outflows to purchase products or services. Occasionally, a company will agree to overpay a vendor for inventory upon purchase, provided the vendor rebates that excess charge with a cash payment in a later period. Recording that cash rebate as revenue is clearly inappropriate, as it should be considered an adjustment to the cost of the inventory purchased. However, our good friends at Sunbeam did not see it that way. Sunbeam played a neat trick to boost revenue in which its advanced cash to vendors and then recorded revenue when that cash was repaid. Additionally, Sunbeam would commit to future purchases from a particular vendor in exchange for an immediate “rebate” from that vendor, which Sunbeam, of course, recorded as revenue.

4. Recording Revenue from Appropriate Transaction, but at Inflated Amounts

Surging revenue growth always wows investors, especially when it occurs in an industry that does not normally grow at breakneck speed. back in 1993, one such darling consulting company, Education Alternatives Inc., enchanted Wall Street with revenue leaping tenfold in a single year. And boy did Wall Street notice, as the firm’s share price doubled in three short months.

Education Alternatives provided consulting services to school boards on topics such as security, maintenance, and improving student performance. The company was tiny, and its business model was simple. Such small and uncomplicated consulting companies rarely present complicated accounting issues for auditors or investors.

Things changed dramatically for the company in 1992, however, when it won a contract to manage the entire budget for nine Baltimore public schools. This was more than a plain-vanilla consulting arrangement. Education Alternatives was charged with improving student performance, and it was given control of the school board’s check book in managing the $133 million budget over the next five years.

How would Education Alternatives be compensated for this unique consulting gig? Let’s start with the $133 million total for the five years. That works out to $26.6 million available to spend each year for the schools. The deal worked as follows: Baltimore would pay no more than the amount allocated in the budget, $26.6 million annually. If, for example, Education Alternatives spent $25 million on the schools, the remaining $1.6 million would be considered its fee. If, instead, it spent the entire $26.6 million (about $5,900 per student), the company would get nothing; and if it went over the budget, the company would have to dig into its pocket to make up the shortfall. It could actually lose money on the deal.

Well when it comes to recognizing revenue, Education Alternatives shunned the traditional consulting revenue model and came up with something that might be considered a bit crazy. The company decided to recognize as its own revenue the entire $26.6 million received each year (or $133 million over five years). As a result, the company’s revenue jumped from approximately $3 million to $30 million in the first year of the contract.

The following year, Education Alternatives hit an even bigger jackpot when the city of Hartford decided to turn the management of its entire school system over to the company. Revenue raced to $214 million in 1995, as Education Alternatives treated the entire budget for Hartford’s schools as though it were its own sales. As a result, revenue that in 1992 had barely reached $3 million climbed to over $200 million in three short years. (Enron executives must have been studying this meteoric revenue rise and taken it upon themselves to outdo Education Alternatives!)

If you spot signs of a questionable accounting approach, test it by comparing the results and practices to those of a similar company that is much larger.

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 3: Boosting Income Using One-Time or Unsustainable Activities:

1. Boosting Income Using One-Time Events

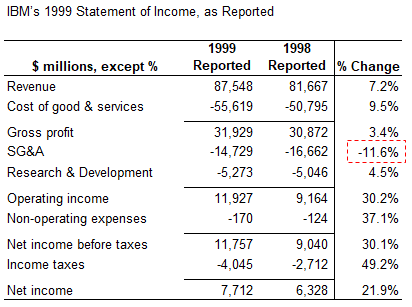

In 1999, IBM was going though a rough patch, as the company’s costs increased faster than revenue. As below table shows, cost of goods and services (COGS) grew 9.5% in 1999, while revenue was up 7.2%, resulting in a lower gross margin. However, somehow IBM’s operating and pretax profits jumped a very impressive 30%.

One thing that should immediately stand out is the 11.6% decline in selling, general and administrative (SG&A) expense, in contrast to the 9.5% increase in COGS. Second, the 30% growth in both operating and pre-tax income seems very surprising on just 7.2% sales growth, unless the company also had a large onetime gain that was hidden from view—or had chosen another shenanigan to boost income or hide expenses.

And that is precisely what happened. A footnote in the 1999 10-K disclosed that IBM booked a $4.057 billion gain from selling its Global Network business to AT&T and curiously included that gain as a reduction in the SG&A expense.

Well Some companies will sell a manufacturing plant or a business unit to another company, and, at the same time, enter into an agreement to buy back product from that sold business unit. Not surprisingly, such transactions that commingle a one-time event (the sale of a business) and normal recurring operating activities (the sale of product to customers) create opportunities for management to use financial shenanigans.

Consider the structure of a November 2006 deal between semiconductor giant Intel Corp. and fellow chip manufacturer Marvell Technology Group. Intel agreed to sell certain assets of its communications and application business to Marvell. At the same time, Marvell agreed to purchase a minimum number of wafers from Intel over the next two years. A careful reading of Marvell’s description of the transaction reveals something odd: Marvell agreed to purchase these wafers from Intel at inflated prices. (Interestingly, Intel did not disclose this, perhaps considering the amount to be insignificant.) Why would Marvell agree to overpay for this inventory?

If Marvell overpaid for the products, it must have underpaid for the business. In other words, Intel probably received less cash up front from the sale of the business in exchange for more cash later in the form of revenue from the sale of product. This certainly works out well for Intel, as a recurring revenue stream impresses investor far more than cash received from the sale of a business.

Hence, make sure to always review both parties’ disclosures on the sale of business of best grasp the true economics of the transactions.

2. Boosting Income through Misleading Classifications

The most common way to shift normal operating expenses below the line involves one-time write-offs of costs that would normally appear in the operating section. For example, a company writes off its inventory or plant & equipment and bring its depreciation down, inflating it operating profits.

If you encounter a company with frequent one-time or restructuring charge listed in its Statement of Income, investigate these charges more closely to understand what exactly the company is trying to keep out of its operating income.

Another fairly easy trick that can magically improve a company’s operating profits starts with an announcement of plans to sell off a money losing division. Consider a struggling company with three divisions producing the following operating results: Division A, $100,000 income; Division B, $250,000 income; and Division C, $400,000 loss. The company would report a $50,000 net loss—unless it had decided to put Division C up for sale at the beginning of the period and account for it as a “discontinued operation.” In so doing, that entire $400,000 loss would be moved below the line and most likely be ignored by investors. Magically, although the company still operates all three divisions at a combined loss of $50,000, it would report all-important operating income of $350,000 and an unimportant $400,000 below the line loss.

For a small investment in a company (typically under 20%), the owner presents the investment at fair value on its Balance Sheet. If the investment is designated as a trading security, changes in fair value are reflected on the Statement of Income. If it is instead designated as available for sale, changes in fair value are presented as an offset to equity, with no impact on earnings (unless permanent impairment exists).

Our friends at Enron understood perhaps better than anyone the benefit of using non consolidated joint ventures to offload debt and losses. In the mid-1990s, Enron began building out a series of new ventures that would require massive infusions of capital and would probably produce large losses during their early years. Management no doubt contemplated the potentially damaging impact of including the debt on the Balance Sheet and the big losses on the Statement of Income. Enron knew that lenders and credit rating agencies would blanch if it showed bulging loans payable, and that investors would be none too pleased with the big losses or earnings dilution if the company used its stock to finance these projects. Since these traditional forms of financing seemed problematic, Enron developed a somewhat unique and certainly very unorthodox strategy. It created thousands of partnerships (ostensibly under accounting rules) that it hoped would not be consolidated and, as a result, would keep all this new debt off its Balance Sheet. Moreover, Enron believed that this complicated structure would also help it hide the expected economic losses (or, whenever possible, pull in gains) from these early-stage ventures.

Interestingly, the capital that Enron contributed to some of these joint ventures turned out to be nothing other than its own stock. In some cases, the partnerships themselves even held Enron stock among their investment holdings. As its stock price jumped over time, the value of the joint venture assets likewise increased, as did Enron’s own equity stake in these partnerships. This trick allowed Enron to recognize approximately $85 million in earnings as a result of nothing more than an increase in its own stock price during a fabulous bull market.

Curiously, when the stock began its rapid descent, Enron must have developed a severe case of amnesia and simply forgotten that the resulting $90 million loss should also be reported to shareholders. Instead, Enron conveniently announced that the results remained “unconsolidated” and, of course, not included on the Statement of Income. So, by Enron’s rules, on the very same investment vehicle, gains get consolidated and losses are hidden from investors’ view. In other words, for Enron it was— heads I win, tails I still win! Well, we all know how that sad story ended.

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 4: Shifting Current Expenses to a Later Period:

Companies account for their costs and expenditures in a two-step accounting dance. Step 1 occurs at the time of the expenditure – when the cost has been paid, but the related benefit has not yet been received. At Step 1, the expenditure represents a future benefit to the company, and is therefore recorded on the Balance Sheet as an asset. Step 2 happens when the benefit is received. At this point, the cost should be shifted from the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Income and recorded as an expense.

1. Improperly Capitalizing Normal Operating Expenses

This section focuses on a very common abuse of the two-step process: management’s taking only one step when two are required. In other words, management improperly records costs on the Balance Sheet as an asset (or “capitalizes” the costs), instead of expending them immediately.

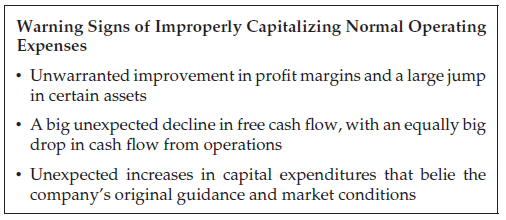

With the technology meltdown beginning in 2000, WorldCom’s revenue growth began to slow, and investors started paying more attention to the company’s large operating expenses. And line costs were, by far, WorldCom’s largest operating expense. So, WorldCom decided to use a simple trick to keep earnings afloat. In mid-2000, it began concealing some line costs through a sudden, and very significant, change in its accounting. (Red flag!) Rather than recording all of these costs as expenses, WorldCom capitalized large portions of them as assets on the Balance Sheet. The company did this to the tune of billions of dollars, which had the impact of grossly understating expenses and overstating profits from mid-2000 to early 2002.

When WorldCom began capitalizing billions in line costs, it clearly continued paying the money out, although the Statement of Income reported fewer expenses. As discussed in part one of the article, a careful reading of the Statement of Cash Flows would have flashed a bright light on deteriorating free cash flow. Below Table shows how free cash flow went from a positive $2.3 billion in 1999 (the year before capitalizing the line costs) to a negative $3.8 billion (an astounding $6.1 billion deterioration). In particular, WorldCom’s large increase in capital spending should have raised questions. It belied WorldCom’s own guidance (given at the beginning of the year) for relatively flat capital expenditures, and it came at a time when technology spending, in general, was collapsing.

Regardless of the legitimacy of an accounting change, investors must strive to understand the impact that this change had on earnings growth. Simply put: any growth related to the change will not recur. In order to be maintained, the growth must be replaced with improved operational performance.

2. Amortizing Costs Too Slowly

Now that we have completed step 1, we have those costs capitalized, but the related benefit has yet to be received. Step 2 involves recording those costs as expenses, shifting them from the Balance Sheet to the Statement of Income.

Consider how Time Warner Telecom changed its depreciable life for fixed assets in 2007. As it described clearly to its investors in a footnote, the company’s March 2007 decision to lengthen the depreciable life on certain assets from 15 to 20 years inflated profits by about $4.9 million in that quarter and was presumed to add a similar amount to quarterly profits for years to come. The $4.9 million represented nearly all of the company’s $5.4 million in operating income that quarter, and an annualized $19.6 million certainly helped the company to improve on the $16.3 million in operating income reported in the previous year.

By comparing depreciation policies with industry norms, investors can determine whether a company is writing off assets over an appropriate time span. Investors should be concerned when a company depreciates its fixed assets too slowly (thereby creating a boost to income), especially in industries that are experiencing rapid technological advances.

Investors should be cautious when they see a company create profits simply by flipping an accounting switch. Let companies generate profits the old-fashioned way—by selling more product and controlling costs!

In most industries, the process of turning inventory into expense is straightforward: when a sale takes place, inventory is transferred to the expense called cost of goods sold. In certain businesses, though, determining when and how inventory turns into expense can be more difficult. In the film business, for example, the costs of making movies or TV programs are capitalized before the films’ release. These costs are then matched (charged as expense) against revenue based on the receipt of revenue. Since revenue may be realized over several years, however, a film company must project the number of years of anticipated revenue flow. If it chooses too long a period, the inventory and profits will be overstated.

3. Failing to Write Down Assets with Impaired Value

This section focuses on freezing the dance between step 1 and step 2 – that is failing to record an expense for costs that had been properly capitalized but that diminished in value before the expected benefit was received. It is not enough for companies to simply depreciate fixed assets on a rigid schedule and assume that nothing can ever happen to change that plan. Management must continuously review these assets for possible impairment and record an expense whenever the assumed future benefits fall below book value.

Companies naturally build up inventory in anticipation of selling product to customers. Sometimes, however, the demand for a product fails to meet a company’s lofty expectations. As a result, the company may have to lower its prices in order to move the less desirable inventory. Or it may have to scrap (write off) the inventory completely. Management must routinely estimate its “excess and obsolete” inventory and reduce its inventory balance accordingly by recording an expense (often called inventory obsolescence expense).

Investors should monitor a company’s inventory level by calculating its days’ sales of inventory (DSI). As this calculation helps investors determine whether an increase in the absolute level of inventory is in line with the overall growth of the business, or whether it might be a harbinger of margin pressure.

Consider the case of women’s clothing retailer Coldwater Creek Inc., whose inventory swelled in the July 2006 quarter. Management told investors not to fret about the higher inventory balance with several justifications, including the need to fill the shelves at the 60 new stores that had opened in the past year. A quick calculation of DSI (98 days versus 78 days the year before), however, revealed that the inventory growth had exceeded the recent growth of the business, a signal of diminished profits in future periods. Moreover, the year-over-year growth in the company’s inventory balance (67.2%) seemed completely unjustified when compared with management’s expectations for revenue growth in the second half of 2006 (24.3%).

Astute investors would have been completely unsurprised when the company reported miserable results at the end of 2006 and throughout 2007. Deeply discounted clothes filled Coldwater Creek stores (including many 90-%-off racks) as the company struggled to move excess inventory. Coldwater Creek’s earnings disappointed Wall Street, and its stock price fell from above $30 per share at the beginning of the 2006 holiday season to below $10 heading into the 2007 holidays.

4. Failing to Record Expenses for Uncollectible Receivables and Devalued Investments

There are two general categories of assets: assets created from costs that management expects to produce a future benefit (e.g., inventory, equipment, and prepaid insurance) and assets created from sales or investments that will be exchanged for an asset such as cash (e.g., receivables and investments). So far, we have discussed on the games played in first category of assets. This section focuses on the second category of assets.

Accounting rules require that certain assets be regularly written down to their net realizable value (accountants’ lingo for the actual amount you expect to get paid). Accounts receivable should be written down each period by recording an estimated expense for likely bad debts. Similarly, lenders should record an expense (or loan loss) each quarter to account for the anticipated deadbeat borrowers. Additionally, investments that experience a permanent decline in value must be written down by recording an impairment expense. Failing to take any of these charges will result in overstated profits.

Investors much always keep an eye if there is a decline in bad debt expense, allowance for doubtful accounts and loan loss reserves, as it could be a sign of management trying to bring down its expenses and hence inflate profits.

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 5: Employing Other Techniques to Hide Expenses or Losses:

1. Failing to Record an Expense from a Current Transaction

A fairly simple way to hide expenses would be to pretend that you never saw an invoice from a vendor until after the quarter has ended.

An example of failing to record end-of-period expenses involves the infamous Symbol Technologies. Symbol paid bonuses to employees in the March 2000 quarter but failed to record the related obligation to pay $3.5 million in Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) insurance. Instead, the company inappropriately decided that it would record the expense in a later period, when the cash was paid. By failing to properly accrue the FICA expense in March, Symbol overstated its quarterly net income by 7.5%.

A less common ploy to artificially reduce expenses and inflate profits involves receiving sham rebates from suppliers. Naturally, this shenanigan needs the assistance of the supplier.

Syntax-Brillian Corp. took the concept of vendor rebates to a completely different and inappropriate level. The company received various vendor credits from its primary supplier (Kolin), which, was also a significant shareholder of the company. Syntax-Brillian recorded these vendor credits as a reduction in cost of goods sold, which naturally provided a benefit to earnings. The problem was, however, that these were no ordinary credits. The size of these credits was absolutely shocking; it accounted for more than all of Syntax-Brillian’s gross profit over its brief history as a public company. Specifically, between December 2005 and June 2007, the company reported gross profit of $142.7 million, which included credits from Kolin totaling an astounding $214.7 million. Moreover, the company never received cash for these credits; they were just bookkeeping entries. As a result, Syntax-Brillian showed decent profitability, but severely negative cash flow from operations. Even novice investors could have identified this scheme. A quick quality of earnings check would have revealed a huge disparity between cash flow and net income.

Always question any cash receipt from a vendor. Cash normally flows out to vendors, not in, so unusual cash inflows from vendors may signal an accounting shenanigan.

Most shenanigans discussed share a common theme: company executives use accounting gimmicks to show impressive results in hopes of driving up the stock price so that their shares and options become very valuable. The options backdating scandal that erupted in 2006 is on a whole different level of dishonesty. Executives were able to skip the whole part about using accounting gimmicks, showing impressive results, and driving up the stock price. Instead, they cut right to the chase and secretly gave themselves stock options that had already increased in value. In so doing, executives found a simple way to loot the company’s coffers without letting anyone know. They thought it was the perfect heist—and it was, until they were caught.

2. Failing to Record an Expense for a Necessary Accrual or Reversing a Past Expense

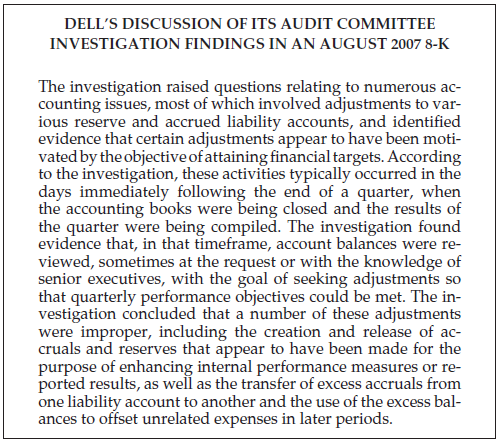

Management sometimes fails to record the necessary expense accruals for expected costs. These accruals are generally company estimates of routine liabilities incurred in normal business operations, such as a manufacturer’s warranty. Often these costs are estimated and recorded at the very end of a quarter. Failing to appropriately record an expense for these costs, or reversing past expenses, will inflate earnings. Since these costs rely on management assumptions and discretionary estimates, all management needs to do to generate more earnings (and achieve Wall Street targets) is to tweak these assumptions.

To illustrate, consider the shenanigans that occurred at Dell Computer from 2003 through the beginning of fiscal 2007. The published findings of a special investigation conducted by Dell’s audit committee in 2007 (as presented here) provide some fantastic, juicy details about Dell’s games with reserves.

A decline in warranty expense or warranty reserve relative to revenue may signal that earnings are being inflated through under accruing for warranty obligations. Monitor these trends quarterly!

Companies often provide helpful detail about their purchase commitments in the footnotes to their financial statements. Investors should always review this disclosure to get a better understanding of a company’s obligations.

3. Failing to Record or Reducing Expenses by Using Aggressive Accounting Assumptions

This technique demonstrates how management’s flexibility in selecting accounting policies and estimates can be a tool for hiding expenses. Companies that provide pensions and other postretirement benefits to employees can change their accounting assumptions in ways that reduce the recorded expense. Similarly, companies that lease equipment make a variety of estimates that will have a bearing on the reported liabilities and expenses. Management can manipulate earnings (and reduce liabilities) by changing accounting or actuarial assumptions.

The pension footnote is required reading for any company with a large pension plan. Investors should monitor key assumptions and assess the impact of pension expense on earnings.

A decline in self-insurance expense as a percentage of revenue should be considered a warning sign and investigated further.

4. Reducing Expenses by Releasing Bogus Reserves from Previous Charges

One benefit of taking a special charge is to inflate future-period operating income because future costs have already been written off through that charge. And second is that the liability created with the charge becomes a reserve that can easily be released into earnings in a later period.

Many of these liability reserves (especially the generic ones) are often grouped in a “soft” liability account sometimes called “other current liabilities” or “accrued expenses.” Investors should monitor soft liability accounts closely and flag any sharp declines relative to revenue. Often, companies discuss these soft liabilities in a footnote. Make sure to find them and track the individual reserves as well.

In the next article, we will discuss on how management uses accounting tricks which inflate future period earnings and cash flows of the company.

Disclaimers :

The information herein is used as per the available sources of bseindia.com, company’s annual reports & other public database sources. Alpha Invesco is not responsible for any discrepancy in the above mentioned data. Investors should seek advice of their independent financial advisor prior to taking any investment decision based on this report or for any necessary explanation of its contents

Future estimates mentioned herein are personal opinions & views of the author. For queries / grievances – support@alphainvesco.com or call our support desk at 020-65108952.

SEBI registration No : INA000003106

Readers are responsible for all outcomes arising of buying / selling of particular scrip / scrips mentioned here in. This report indicates opinion of the author & is not a recommendation to buy or sell securities. Alpha Invesco & its representatives do not have any vested interest in above mentioned securities at the time of this publication, and none of its directors, associates have any positions / financial interest in the securities mentioned above.

Alpha Invesco, or it’s associates are not paid or compensated at any point of time, or in last 12 months by any way from the companies mentioned in the report.

Alpha Invesco & it’s representatives do not have more than 1% of the company’s total shareholding. Company ownership of the stock : No, Served as a director / employee of the mentioned companies in the report : No. Any material conflict of interest at the time of publishing the report : No.

The views expressed in this post accurately reflect the authors personal views about any and all of the subject securities or issuers; and no part of the compensations, if any was, is or will be, directly or indirectly, related to the specific recommendation or views expressed in the report.

Stay Updated With Our Market Insights.

Our Weekly Newsletter Keeps You Updated On Sectors & Stocks That Our Research Desk Is Currently Reading & Common Sense Approach That Works In Real Investment World.