Disclaimer: The Blog on ‘Financial Shenanigans’ is not a recommendation to buy / hold / sell any stock. The published post is for information purpose only. Please read the detailed disclaimer at the bottom of the post.

Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance Or Economic Health By Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 3

Below article is follow up of the article – “Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance Or Economic Health By Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 2”. You can read the previous parts of the article – Part 1 (Link) & Part 2 (Link)

In the previous article we looked at five important earning shenanigans used by managements to inflate their current period earnings. In this article we will look at couple of other shenanigans used by managements to inflate future period earnings.

Inflating Future Period Earnings :

To inflate tomorrow’s operations, management would simply hold back today’s revenue or gains and accelerate tomorrow’s expenses or losses into the current period. Now you might be thinking why would a company want to report smaller profits? Consider a company that is growing like gangbusters and is unsure of what tomorrow holds, or one that has benefited from a large windfall gain or a huge new contract. Investors surely would love to see those delicious numbers, but they also would naturally expect management to duplicate or even exceed them tomorrow. Meeting those unrealistically high investor expectations may be virtually impossible, leading management to feel compelled to use this technique. Below shenanigans can be categorized in this subgroup:

EM 6 – Shifting Current Income to a Later Period

EM 7 – Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 6: Shifting Current Income to a Later Period:

1. Creating Reserves and Releasing Them into Income in a Later Period

Companies must report revenue’s only when (1) evidence of an arrangement exists, (2) delivery of the product or services has occurred, (3) the price is fixed or determinable, and (4) payment is reasonably assured. EM Shenanigan No. 1 focused on recording revenue too early by failing to wait for the completion of these requirements. As a result, revenue and net income would be inflated.

When business is booming and earnings far exceed Wall Street estimates, companies may be tempted not to report all their revenue, but instead to save some of it for a rainy day. Consider a situation in which management refuses to record some revenue that was rightfully earned during the current period, instead storing it on the Balance Sheet with all the legitimately recorded unearned revenue until it is needed during a later period. This is really simple to do, and the auditors may not even question the move, as they may consider it “more conservative.”

Consider the Florida based chemical company W. R. Grace. In the early 1990s, Grace’s health-care subsidiary experienced a significant and unanticipated increase in revenue as a result of changes in Medicare reimbursements. Management deferred some of the unanticipated income by increasing or establishing reserves. These reserves ballooned to more than $50 million by the end of 1992. By creating these reserves and then releasing some of them, the subsidiary reported steady earnings growth of from 23 to 37 percent between 1991 and 1995. The actual growth rates ranged from minus 8 percent to plus 61 percent. When Grace sold this subsidiary in 1995, it released the entire excess reserve into income, labelling it a “change in accounting estimate.” Alert investors should have considered that earnings boost unsustainable.

Enron’s infamous manipulation of the California energy markets in 2000–2001 earned the company huge windfall profits in its trading division. The profits were so large that management decided to save some for future quarters, which, according to the SEC, was done in order to mask the extent and volatility of its windfall trading profits. Compared to the rest of Enron’s shenanigans, this scheme was fairly straightforward: simply defer some of the trading gain by storing it in a reserve on the Balance Sheet. These reserves came in handy and helped Enron avoid reporting large losses during difficult periods. By early 2001, Enron’s undisclosed reserve accounts had ballooned to over $1 billion. The company then improperly released hundreds of millions of dollars of these reserves to ensure that Wall Street’s expectations were met. Ironically, there would be no future quarters in which to release unused reserves, as Enron imploded in October 2001 and probably needed to show all the revenue that it had held back for the rainy day. That rainy day surely had arrived in October 2001—a Category Five hurricane for investors, with no survivors!

Smoothing of income is not an uncommon strategy for management to engage in, as Wall Street rewards solid and predictable profit growth. However, the use of reserves to shift income to a later period can be as serious an income manipulation ploy as recording revenue too soon. In both cases, the effect is misleading financial results. When revenue is recorded too early, future income is recorded in the current period; conversely, with income smoothing, current income is shifted to a future period.

2. Improperly Accounting for Derivatives in Order to Smooth Income

Companies with healthy businesses can engage in income-smoothing shenanigans to give the illusion of nice, steady, predictable results. Consider mortgage giant Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac or Freddie) and its desire to portray very smooth earnings despite a period of volatile interest-rate movements. Freddie’s attempts to smooth earnings went to the extreme and led to an over $5 billion fraud.

Freddie’s earnings manipulation was related largely to its incorrect accounting for derivative instruments, loan origination costs, and reserves for losses. From 2000 to 2002, Freddie Mac under reported net income by nearly $4.5 billion. Freddie’s smoothing techniques allowed it to report earnings growth of 63 and 39% in 2001 and 2002, when in reality, earnings growth was a much more volatile negative 14% in 2001 and positive 220% in 2002.

Well, Wall Street had come to expect steady and predictable earnings from the company. A challenge arose in 2000 with the implementation of a new accounting rule that created enormous volatility in the company’s investment activities involving derivatives. It quickly became clear to management that the change in accounting would create huge windfall gains for the company. Initial estimates of the gain were in the hundreds of millions, but they soon ballooned to the billions. For most of us, billions of dollars in windfall gains would be great news. To Freddie Mac, however, this was a problem. The company’s rock-solid stock price was largely built on its ability to produce steady and predictable earnings. It certainly earned its nickname “Steady Freddie.” So, ever conscious of its reputation for pleasing Wall Street, Freddie schemed to hold back a large part of the windfall gain and release portions of it when needed to smooth earnings.

Investors should be cautious when a company reports large gains from hedging activities, as these ineffective (sometimes called economic) “hedges” may really be unreliable speculative trading activities that could just as easily produce large losses in future periods. In addition, investors should look out for ineffective hedges that produce gains well in excess of the loss in the underlying asset or liability. Consider Washington Mutual Inc., with its history of presenting large gains on activities that it characterized as hedging. In 2004, the company reported $1.6 billion in gains that were classified as “economic hedges” against a $500 million loss from its unhedged MSR (mortgage servicing rights) asset. In other words, Washington Mutual’s hedging activities resulted in gains that were three times the size of the underlying loss. Investors should also be wary of “hedges” that move in the same direction as the underlying asset or liability, as this may signal that management is using derivatives to speculate, not to hedge.

3. Creating Reserves in Conjunction with an Acquisition and Releasing Them into Income in a Later Period

As we have pointed out previously, acquisitive companies create some of the biggest challenges for investors. For one thing, the combined companies immediately become more difficult to analyse on an apples-to-apples basis. Second, acquisition accounting rules create distortions in the presentation of cash flow from operations. And finally, companies that are making acquisitions might be tempted to have the target company hold back some revenue that was earned before the deal closes so that the acquirer can record it in the later period.

Imagine that you recently signed an agreement to sell your business, with the closing to be in two months. You also receive instructions to refrain from recording any more revenue until the merger is consummated. Somewhat baffled, you comply and record no more revenue. In so doing, you have made a friend for life, as the two months of revenue you held back will be released by the acquiring company. Inflating revenue right after closing on an acquisition is a pretty simple trick: once the merger is announced, instruct the target company to hold back revenue until after the merger closes. As a result, the revenue reported by the newly merged company improperly includes revenue that was earned by the target before the merger.

Remember our friends at Computer Associates who manipulated their numbers to help senior management take home $1 billion in bonuses? We pointed out some of the many tricks the company used to accomplish this feat, including the “35-day” month and immediate revenue recognition on 10-year installment sale contracts. Computer Associates may have also benefited from revenue that was held back before an acquisition.

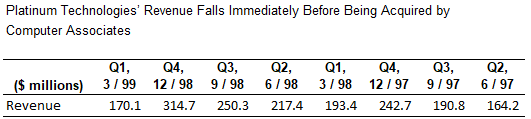

Consider, for example, Computer Associates’ 1999 purchase of Platinum Technologies. During the March 1999 quarter, the last one before the deal closed, Platinum’s revenue plunged to its lowest level in seven quarters, falling by more than $144 million sequentially and by more than $23 million from the year-ago period (see Table). Platinum attributed the sharp decline to delays in closing customer contracts as a result of its proposed acquisition by Computer Associates. Whatever the real reasons, however, Platinum’s failure to close these sales provided its new owner with an artificial revenue boost. Taking the analysis one step further, even if Platinum’s revenue drop-off was not the result of holding back revenue, investors should still be concerned that Computer Associates was buying a business with rapidly shrinking revenue.

4. Record Current-Period Sales in a Later Period

This section could be considered a close cousin of the previous one: holding back revenue until a later period. The previous section explored this game in the context of acquisitions. In this section, we discuss a simple trick that is less fancy: management simply decides to record the sale after the period closes, thereby holding back revenue until the later period.

Assume that late in a very strong period, management has achieved all the earnings targets needed to reach its maximum bonuses for the period. Sales continue at a brisk pace, and management has an idea that will ensure high bonus payments for the next period as well—stop recording any more sales and shift them to the next quarter. It is simple to do, it is unlikely that the auditors will even know about this trick, and your customers certainly won’t object, since they will get billed later than they expected. Nonetheless, this practice is dishonest and misleading to investors, as it portrays higher sales in the later period. More important, however, it shows that management makes business decisions that are based not on sound business practices, but on dressing up its financial reports for investors.

Earnings Manipulation Shenanigan No. 7: Shifting Future Expenses to an Earlier Period:

1. Improperly Writing Off Assets in the Current Period to Avoid Expenses in a Future Period

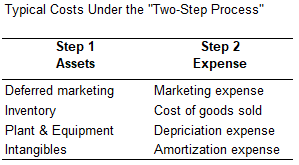

In the previous article – EM Shenanigan No. 4, showed the first way to bungle the two-step dance – by shifting from step 1 to step 2 far too slowly, or perhaps not at all. In this section we will discuss another inappropriate way to dance the two-step that is actually the opposite of the dance discussed in EM Shenanigan No. 4 – simply shift costs from step 1 to step 2 immediately. In other words, write off assets by recording expenses much earlier than is warranted.

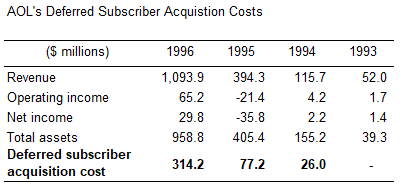

Consider Internet pioneer AOL and its accounting treatment of solicitation costs during its critical mid-1990s growth years. AOL was struggling to show a profit and had begun capitalizing marketing and solicitation costs in order to push the company into the black. The company inflated profits by capitalizing normal expenses on the Balance Sheet and further stretched out the amortization period for these costs from one to two years; this further muted the expenses and inflated profits.

AOL had accumulated more than $314 million in the asset account labelled deferred subscriber acquisition costs (DSAC). But the company still had a big problem: those costs represented tomorrow’s expense, and they would need to be amortized over the next eight quarters—a $40 million hit to earnings each quarter. Considering AOL’s modest earnings level ($65.2 million in operating income in fiscal 1996), a recurring $40 million quarterly charge would be, to put it mildly, quite unwelcome.

So, three months later, when its DSAC asset had ballooned to $385 million, AOL shifted to Plan B and started playing its version of the opposite game. Rather than continuing with the two-step dance and amortizing the marketing costs over the next eight quarters, AOL switched gears and announced “a one-time charge” to write off the entire amount in one fell swoop. Of course, it had to come up with a justification to convince the auditors that this asset account had suddenly become impaired and would provide no future benefit. So, AOL stated that the write-off was necessary to reflect changes in its evolving business model, including reduced reliance on subscribers’ fees as the company developed other revenue sources. To say that we were skeptical of this explanation would be an understatement.

Also, during the technology bust in 2000, many companies properly wrote off impaired assets, including inventory, plant and equipment, and intangibles. Cisco System Inc.’s $2.25 billion inventory write-off in April 2001, however, stood out from the pack as unusual. This inventory charge seemed massive in isolation, but upon closer inspection and compared with the most recent quarter’s cost of goods sold, we really understood the magnitude of that number: the amount written off represented more than 100 percent of that entire quarter’s inventory sales. Turn the clock ahead a quarter or two to when the economy started to improve, and Cisco’s revenue returned to normal levels. Assuming that Cisco chose not to throw all of those written-off routers in the trash when taking the onetime charge (probably a pretty safe assumption), the company then would have reported sales with an inflated profit margin.

Similarly, writing off assets would reduce future-period depreciation and amortization expense and increase net income.

2. Improperly Recording Charges to Establish Reserves Used to Reduce Future Expenses

A similar trick in which companies record an expense today in order to keep future expenditures from being reported as expenses. With this trick, management loads up the current period with expenses, both taking some from future periods and even making some up. In so doing, when the future period arrives, (1) operating expenses will be under reported, and (2) bogus expenses and the related bogus liabilities will be reversed, resulting in under reported operating expenses and inflated profits.

In December 2000, Symbol Technologies recorded $185.9 million in charges in connection with its purchase of competitor Telxon Corporation. At the time, Symbol justified these charges as being necessary for restructuring of operations, impairment of assets (including inventory), and merger integration costs. It turns out that the charges improperly included fictitious costs that were used to create cookie jar reserves to help inflate earnings in future periods. The charges also overstated inventory write-offs that would provide a boost to future gross margins as the related inventory was sold.

There is no better time to record huge charges than when the market is in a downturn. Since during these times investors are more focused on how companies will emerge from the downturn, large charges are rarely frowned upon; indeed, they are often seen as a positive. Amazingly, during the 2002 market slump, 40 of the 54 largest U.S. utility companies (74 percent) recorded unusual charges (according to a survey by CFRA). Plus, it is not difficult for management to use these charges to inappropriately write off productive assets or establish bogus reserves.

This ends our discussion of the seven Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans. As EM Shenanigans No. 1 through 5 (Article No.2 of the series) illustrated, management has a large arsenal of techniques that can trick investors into believing that a company has generated more profit than it really has. And if management instead desires to make tomorrow look fantastic, EM Shenanigans No. 6 and 7 (Article No. 3 of the series) will get the job done.

Well managements today have expanded their playing field of deception beyond Earnings Manipulation Shenanigans. Our next article will focus on how management misrepresent its cash flow statement and how investors can identify these tricks.

Disclaimers :

The information herein is used as per the available sources of bseindia.com, company’s annual reports & other public database sources. Alpha Invesco is not responsible for any discrepancy in the above mentioned data. Investors should seek advice of their independent financial advisor prior to taking any investment decision based on this report or for any necessary explanation of its contents

Future estimates mentioned herein are personal opinions & views of the author. For queries / grievances – support@alphainvesco.com or call our support desk at 020-65108952.

SEBI registration No : INA000003106

Readers are responsible for all outcomes arising of buying / selling of particular scrip / scrips mentioned here in. This report indicates opinion of the author & is not a recommendation to buy or sell securities. Alpha Invesco & its representatives do not have any vested interest in above mentioned securities at the time of this publication, and none of its directors, associates have any positions / financial interest in the securities mentioned above.

Alpha Invesco, or it’s associates are not paid or compensated at any point of time, or in last 12 months by any way from the companies mentioned in the report.

Alpha Invesco & it’s representatives do not have more than 1% of the company’s total shareholding. Company ownership of the stock : No, Served as a director / employee of the mentioned companies in the report : No. Any material conflict of interest at the time of publishing the report : No.

The views expressed in this post accurately reflect the authors personal views about any and all of the subject securities or issuers; and no part of the compensations, if any was, is or will be, directly or indirectly, related to the specific recommendation or views expressed in the report.

Stay Updated With Our Market Insights.

Our Weekly Newsletter Keeps You Updated On Sectors & Stocks That Our Research Desk Is Currently Reading & Common Sense Approach That Works In Real Investment World.