Disclaimer: The Blog on ‘Financial Shenanigans’ is not a recommendation to buy / hold / sell any stock. The published post is for information purpose only. Please read the detailed disclaimer at the bottom of the post.

Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance or Economic Health by Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 4

Below article is follow up of the article – “Financial Shenanigans – How A Management Can Mislead Its Investors About A Company’s Financial Performance or Economic Health by Using Few Accounting / Financial Reporting Tricks – Part 2”. You can read the previous parts of the article – Part 1 (Link), Part 2 (Link) & Part 3 (Link)

With so many recent financial frauds going undetected, investors are increasingly questioning the value of the accrual-based figures shown on the Statement of Income. Time and time again, companies have duped investors by recording revenue too soon or hiding expenses. Some sophisticated investors claim that they realize that earnings can be manipulated and therefore put more faith in the purer cash flow from operations.

The book discusses four specific types of Cash Flow (CF) Shenanigans, discussing techniques that management employs to inflate reported cash flow from operations (CFFO), a particularly important metric that investors rely upon to assess both a company’s ability to generate cash and its quality of earnings.

CF Shenanigan No. 1: Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

CF Shenanigan No. 2: Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

CF Shenanigan No. 3: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

CF Shenanigan No. 4: Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

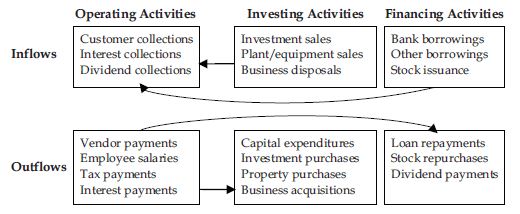

Before diving into these Cash Flow Shenanigans, it is important to understand the basic structure of the Statement of Cash Flows. All cash movements can be grouped into one of three categories: Operating, Investing, and Financing activities. Investors do not consider the three sections of the Statement of Cash Flows equally important. Rather, they regard the Operating section as the “favoured son” because it presents cash generated from a company’s actual business operations. Many investors are less concerned with a company’s investments or capital structure, and some even go to the extreme and completely ignore the other sections. Because of which companies try to move all the good stuff (cash inflows) to the operating section and send the bad stuff (cash outflows) to the less important Investing and Financing sections. Below figure illustrates some of these tricks, such as improperly moving inflows that really came from bank borrowings to the Operating section or shifting those unwanted outflows out of Operating and labelling them capital expenditures.

Well lets now look at these cash flow shenanigans one by one:

CF Shenanigan No. 1: Shifting Financing Cash Inflows to the Operating Section

1. Recording Bogus CFFO from a Normal Bank Borrowing

At the end of 2000, Delphi Corporation found itself in a bind. It had been spun out from General Motors (GM) a year earlier, and management was intent on showing the company to be a strong and viable stand-alone operation. However, despite management’s ambitions, all was not well at the auto parts supplier. Since the spinoff, Delphi had cooked up many schemes to inflate its results. The auto industry was reeling, and the economy was getting worse.

Delphi’s operations continued to deteriorate in the fourth quarter of 2000, and the company was facing the prospect of having to tell investors that cash flow from operations had turned severely negative for the quarter. This would have been a devastating blow, as Delphi often highlighted its cash flow in the headline of its earnings releases as a key indicator of the company’s performance and its (purported) strength.

So, already knee-deep in lies, Delphi concocted another scheme to save the quarter. In the last weeks of December 2000, Delphi went to its bank (Bank One) and offered to sell it $200 million in precious metals inventory. Not surprisingly, Bank One had no interest in buying inventory. Remember, we are talking about a bank, not an auto parts manufacturer. Delphi understood this and crafted the agreement in such a way that Bank One would be able to “sell” the inventory back to Delphi a few weeks later (after year-end). In exchange for the bank’s “ownership” of the inventory for a few weeks, Delphi would buy it back at a small premium to the original sale price.

Rather than recording the transaction in a manner consistent with the economics and intent of the parties, as a loan, Delphi brazenly recorded it as the sale of $200 million in inventory. In so doing, Delphi inflated revenue and earnings. Moreover, it also overstated CFFO by the $200 million that Delphi claimed to have received in exchange for the sale of inventory. Without this $200 million, Delphi would have recorded only $68 million in CFFO for the whole year (rather than the $268 million reported), including a dismal negative $158 million in the fourth quarter.

If you suspect a company of recording bogus revenue, you must also consider that it may also have recorded bogus operating cash flow.

Consider, Enron, We have already outlined several ruses perpetrated by Enron, particularly its use of off-balance-sheet vehicles such as special purpose entities. Some of the schemes that Enron concocted helped it present a misleadingly stronger CFFO. For example, Enron would create such a vehicle and then help it borrow money by co-signing its loans. The Enron-controlled vehicle then used the cash received to “purchase” commodities from Enron. Enron recorded the cash received as an Operating section inflow (CFFO) from the “sale” of the commodities.

The structure of these transactions may seem complicated, but the economics were quite simple: Enron entered into arrangements to sell commodities to itself. The problem was that it recorded only half of the transaction—the part that reflected the cash inflows. Specifically, Enron recorded the “sale” of the commodities as an Operating inflow but ignored the offsetting outflow from the vehicle’s “purchase” of these commodities. If Enron had recorded this transaction in line with its economics, the cash inflow would have been deemed a loan and hence recorded as a Financing inflow. This trick allowed Enron to embellish its CFFO by billions of dollars, to the detriment of its Financing cash flow—and, of course, of its investors.

2. Boosting CFFO by Selling Receivables Before the Collection Date

Companies often sell accounts receivable as a useful cash-management strategy. These transactions are actually quite simple: a company wishes to collect on its receivables before they come due. The company finds a willing investor (often a bank) and transfers the ownership of some receivables to it. In return, the company pockets a cash payment for the total amount of receivables, less a fee.

In 2004, pharmaceutical distributor Cardinal Health needed to generate a lot more cash. So, management decided to sell accounts receivable to help the company raise a substantial amount of cash very quickly. By the end of the second quarter (December 2004), Cardinal Health had sold $800 million in customer receivables. This transaction was the primary driver of the company’s robust $971 million in CFFO growth in December 2004 over the prior-year period.

While Cardinal Health certainly was entitled to any cash received in exchange for its accounts receivable, investors should have realized that this was an unsustainable source of CFFO growth. Cardinal Health essentially collected on receivables (from a third party, rather than from its customers) that would normally have been collected in future quarters. By collecting the cash earlier than anticipated, the company essentially shifted future-period cash inflows into the current quarter, leaving a “hole” in future-periods’ cash flow. The transfer of cash flow to an earlier period is likely to result in disappointing future CFFO— unless, of course, management finds another CF Shenanigan to plug the hole.

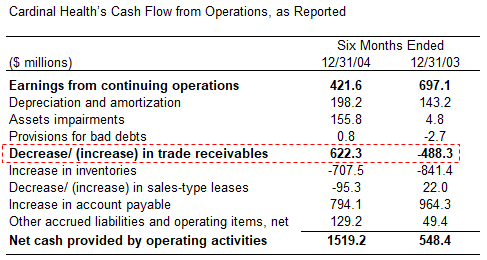

Even novice investors could have identified that something important had changed in Cardinal Health’s accounts receivable, and that CFFO growth was largely driven by this change. Look at the company’s Statement of Cash Flows below Notice that the $971 million increase (from $548 million to $1.5 billion) in CFFO had been driven primarily by a $1.1 billion “swing” in the impact of receivables. Specifically, in the six months ending December 2004, the change in accounts receivable represented a cash inflow of $622 million, while in the previous year, the change in accounts receivable had contributed a cash outflow of $488 million. Without doubt, the massive receivable sale, not an improvement in Cardinal Health’s core business, produced the impressive CFFO improvement. To emphasize, investors should focus not only on how much CFFO grew, but also on how it grew—a very big difference.

When normalizing CFFO to exclude the impact of sold receivables, use the change in sold receivables outstanding at the end of the quarter. This way, you account for the receivables that were outstanding last quarter, but collected during this one.

3. Inflating CFFO by Faking the Sale of Receivables

In previous section we understood that in many cases, selling receivables may be not only appropriate, but also a prudent business decision. However, investors also need to understand that the cash flow that was expected in a future period has now been collected, and that this inflow should be viewed as unsustainable. In this section, we take a step into more nefarious territory. We will encounter another top-secret procedure being performed in the companies’ Twins labs: faking the sale of receivables.

Peregrine embellished its revenue in the years leading up to its 2002 bankruptcy, using deceptive practices such as recording bogus revenue and entering into reciprocal transactions. All of this fake revenue resulted in bloated receivables on the Balance Sheet that would never be collected. Peregrine became concerned that these bloated receivables would become the smoking gun of its bogus revenue. So, the coverup began in earnest with fake sales of accounts receivable.

In this cover-up, Peregrine transferred its receivables to a bank in exchange for cash; however, the risk of collection loss remained with Peregrine. That collection risk was huge, of course, because there were no customers—many of the related sales were bogus. Since the risk of loss had not been transferred, Peregrine remained on the hook to return the cash to the bank when the receivables inevitably were not collected.

Since the receivables had never actually been transferred, the economics of this transaction would be more akin to a collateralized loan, just as we saw with Delphi earlier in this chapter. Peregrine borrowed money from the bank and used receivables as collateral. On the Statement of Cash Flows, this should be presented as a Financing inflow. Peregrine, however, ignored the economic reality of the situation. Instead, it recorded the transaction as the sale of receivables, and shamelessly reported the cash received as an Operating inflow.

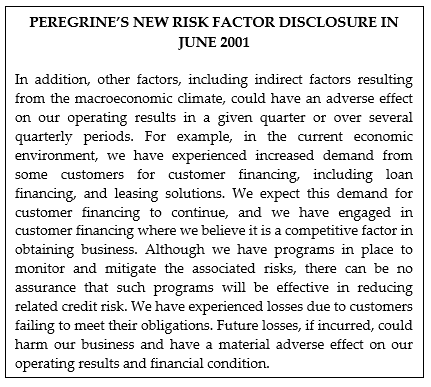

Many investors overlook the “Risk Factor” section of corporate filings because it seems like legal boilerplate. Warning to investors: ignore the risk factors at your own peril. While most of the text may be similar from quarter to quarter, investors should carefully try to identify changes in the verbiage. If new risks have been added or previously listed ones have been changed, then the change is deemed worthy of disclosure by the company or its auditors, and you need to know about it.

For instance, in 2001, the year before Peregrine imploded in fraud, the company inserted an important new risk factor disclosure that should have awakened investors from their slumber. Peregrine actually changed its risk factor disclosure twice, first in June 2001 and then again in December 2001. The new disclosure in June 2001 informed readers that Peregrine was engaging in new customer financing arrangements, including loan financing and leasing solutions. It also reported that some customers were failing to meet their obligations. The mere fact that this disclosure found its way into the risk factors tells you that it must have been significant.

CF Shenanigan No. 2: Shifting Normal Operating Cash Outflows to the Investing Section

In this section we’ll discuss the following two primary techniques that companies use to shift these operating cash outflows to the Investing section.

1. Inflating CFFO with Boomerang Transactions

Global Crossing was one of the highest-flying technology companies during the 1990s dot-com bubble. It was building an undersea fiber-optic cable network that would connect more than 200 cities across four continents, and investors appeared to be absolutely giddy over its prospects. However, as the project neared completion in 2000 and early 2001, critics began to wonder whether Global Crossing would ever sell enough network capacity to recoup the extensive costs of the project and pay down its massive debt.

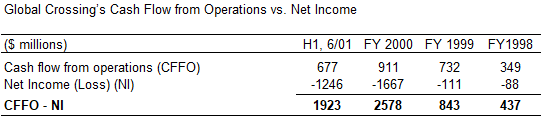

When questioned, Global Crossing always seemed to have a great rebuttal for these naysayers: “Look at all the cash we are generating.” Global Crossing had entered into many substantial contracts in which it sold future capacity and received cash from customers up front—and it had the CFFO to prove it. In 2000, despite a negative $1.7 billion in earnings, the company reported to investors a positive $911 million in operating cash flow. Some of the differential was legitimate. However, a sizeable portion related to boomerang scheme to manipulate its CFFO.

As the technology industry was facing a slowdown, Global Crossing and other telecom players came up with a plan to effectively sell products to each other and, in so doing, boost revenue. From a purely economic standpoint, it was like taking money out of your right pocket and putting it into your left: nothing really changed.

Here’s how it worked: Global Crossing sold large blocks of future network capacity to telecom customers. At the same time, the company purchased a similar dollar amount of capacity from these same customers. In other words, Global Crossing would sell capacity to a customer and simultaneously buy a similar amount of capacity on a different network. This was a classic boomerang transaction. You can almost picture some Global Crossing executive telling the company’s customers, “You scratch my back, and I’ll scratch yours.”

So, what does this have to do with cash flow? Well, Global Crossing recorded these boomerang transactions in a way that artificially inflated CFFO. The company recorded the cash that it received from its customers in these transactions as an Operating inflow; however, the cash that it paid to the same customers was recorded as an Investing outflow. Essentially, Global Crossing inflated cash flow from operating activities by depressing cash flow from investing activities. This allowed the company to show strong CFFO that clearly was well in excess of the economic reality of the transaction. It mattered little that the overstated CFFO was offset by understated cash from investing activities, because CFFO was the key cash flow metric on which investors were focused.

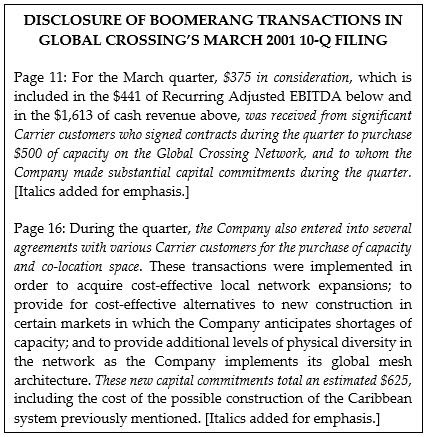

Diligent investors should be able to detect these transactions most of the time; look for disclosure of them in 10-Q and 10-K filings, but don’t expect that companies will use the term boomerang. Of course, companies will make investors work to find them and certainly will not present them on a silver platter. However, there are often plenty of details about these transactions, particularly when they are substantial in size. Consider Global Crossing’s disclosure of its boomerang transactions in its March 2001 10-Q filing:

2. Improperly Capitalizing Normal Operating Costs

Recording normal operating costs as an asset rather than as an expense sounds simple, and frankly, it is quite easy to do. However, it is one of the scariest and most lethal shenanigans out there. Why? Because it is a simple sleight of hand that does more than just embellish earnings—it inflates operating cash flow as well.

Recall our discussion of how WorldCom improperly inflated its earnings by recording its line costs (a clear operating expense) as an asset rather than as an expense? This simple tactic helped the company portray itself as a profitable company rather than tell investors that trouble was stirring. This move also allowed WorldCom to present strong operating cash flow. Purchases of capital assets (called “capital expenditures”) are classified on the Statement of Cash Flows as Investing activities.

This line cost scheme artificially inflated WorldCom’s CFFO by nearly $5 billion in 2000 and 2001, according to the company’s restatement. Together with other improperly capitalized costs and CFFO boosts, WorldCom’s operating cash flow was overstated by a whopping $8.588 billion over these two years

Dishonest company executives may find ways to improperly capitalize any normal operating cost; however, the most common ones are generally those related to long-term arrangements, such as research and development, labour and overhead related to a long-term project, software development, and costs to win contracts or customers. Monitor these accounts for the best chance of spotting aggressive capitalization. Also, when a company improperly records costs as an asset instead of an expense, CFFO will be overstated. Calculating free cash flow reveals the extent of the company’s problems.

CF Shenanigan No. 3: Inflating Operating Cash Flow Using Acquisitions or Disposals

1. Inheriting Operating Inflows in a Normal Business Acquisition

The cash flow shifting tricks in this section have many similarities to the ones we discussed in the previous section; they represent shifts between the Operating and the Investing sections. However, this section we focus on shifts that are related specifically to acquisitions and disposals.

A quirk in the accounting rules gives many companies a benefit to CFFO just for making an acquisition. A company that is growing organically will incur CFFO outflows (payments for creating and marketing products) in order to create CFFO inflows (receipts from customers). However, a company that is growing by acquiring other businesses generates growth without the stigma of those initial CFFO outflows.

To understand why, realize that cash spent to acquire another business runs through the Investing section of the Statement of Cash Flows (SCF) (of course, stock issued for an acquisition does not impact the SCF at all). As a result, when buying another business, companies inherit a brand-new stream of cash flows without having to incur a CFFO outflow. Moreover, by liquidating the working capital of the acquired business, a company can provide itself with an unsustainable CFFO boost. These accounting nuances are why companies that grow through acquisitions often appear to have stronger CFFO than companies that grow organically.

For some companies, these pure boosts to cash flow are just not enough. They want to squeeze even more juice out of these acquisitions. Consider the following scenario, based on allegations in legal proceedings of Tyco’s behaviour during the acquisition process.

Imagine that you work in the accounting department of a company that just announced that it was being bought by a serial acquirer. The acquisition has not officially happened yet, but it is a friendly takeover with lucrative terms, and the deal is likely to close before the end of the month. The new owners want to start coordinating operations. In walks one of the finance executives from the acquirer. He calls a meeting with the team and discusses some logistics that he says will help the transition go more smoothly. He points to a pile of checks—payments from customers that you had planned to deposit later that day. “You see all those checks? I know you normally deposit them at the end of the day, but let’s hold off on that for now. Put them in this drawer, and we’ll deposit them in a few weeks. And let’s call up our biggest customers and tell them that they can hold off on paying us for a few weeks. I know that sounds odd, but this will score us some points and ensure that they stay loyal through the transition. “ And you see that pile of bills? I know you normally wait until the deadline approaches to pay them; however, let’s pay them down ASAP. In fact, see if you can prepay any vendors or suppliers— I’m sure those folks would be willing to take our money and perhaps even give us a discount. We certainly have enough cash in the bank; let’s put it to good use.”

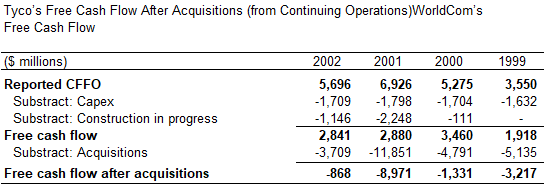

Since acquisitions create an unsustainable boost to CFFO, investors should not blindly rely on CFFO as a barometer of performance. Use free cash flow after acquisitions to assess cash generation at acquisitive companies. Below table shows that Tyco recorded negative free cash flow after acquisitions each year, despite reporting positive CFFO; this was a warning that operating cash flow was not what it appeared to be.

2. Acquiring Contracts or Customers Rather Than Developing Them Internally

Witness Tyco (again) and its electronic security monitoring business. Home security monitoring was a fast-growing business in the 1990s, and Tyco’s ADT division proved to be among the most popular brand names. Tyco generated new security systems contracts in two ways: through its own direct sales force and through an external network of dealerships. The dealers allowed Tyco to outsource a portion of its sales force. They were not on Tyco’s payroll, but they sold security contracts, and Tyco paid them about $800 for every new customer.

Oddly, Tyco executives did not view these $800 payments to dealers to be normal customer solicitation costs, as the economics would suggest. Instead, they deemed these payments to be a purchase price for the “acquisition” of contracts. Thus, after the dealer presented Tyco with a number of contracts and received payment, Tyco curiously accounted for these “contract acquisitions” in the same way that it accounted for normal business acquisitions: as Investing outflows.

Again, calculating free cash flow after acquisition would have given a clear picture of Tyco’s position.

3. Boosting CFFO by Creatively Structuring the Sale of a Business

In this next section, we discuss the flip side of that coin: how companies use disposals to shift cash inflows from the Investing section to the Operating section.

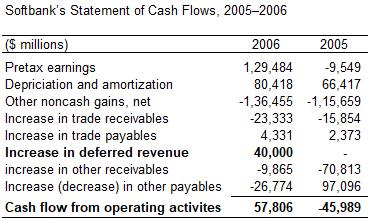

In 2005, Softbank structured an interesting two-way arrangement with a fellow Japanese telecom company, Gemini BB. Softbank sold its modem rental business to Gemini, and simultaneously, the companies entered into a “service agreement” in which Gemini would pay Softbank royalties based on the modem rental business’s future revenue. At the time of the sale, Softbank received ¥85 million in cash from Gemini, but it did not consider the entire amount to be related to the sale price of the business, according to a report by Risk-Metrics Group. Instead, Softbank decided to split the cash received into two categories: ¥45 million was allocated to the sale of the business, and ¥40 million was deemed to be an “advance” on the future royalty revenue stream. This ¥40 million boost to CFFO represented 69 percent of Softbank’s ¥57.8 million in CFFO for the full year.

Investors could easily have spotted Softbank’s CFFO boost just by looking at the Statement of Cash Flows. Take a look at below table and note that a new line item surfaced in 2006—a ¥40 million “increase in deferred revenue.” This Statement of Cash Flows disclosure, together with the magnitude of its impact on CFFO, would be reason enough for astute investors to dig deeper.

CF Shenanigan No. 4: Boosting Operating Cash Flow Using Unsustainable Activities

Struggling companies often use valuable lifelines to help them keep their cash flow afloat. It is often wise and certainly legitimate for companies to use these lifelines. However, companies may fail to disclose the use of these nonrecurring cash flow lifelines. It is up to you to spot them, because once they’re gone, they’re gone. In this section we will discuss four unsustainable lifelines that companies use to boost their cash flow from operations (CFFO).

1. Boosting CFFO by Paying Vendors More Slowly

Want to save a little more cash this year? Use your “delay payments” lifeline: wait until the beginning of January to pay your December bills. If you push your payments out a month, your end of the year bank balance will be higher, and it will cosmetically seem as if you generated more cash this year. However, you certainly would not be under the delusion that you had found a recurring way to grow your cash flow each year; rather, you would realize that this was a one-time benefit. To grow your cash flow again next year, you would have to push two months’ worth of payments into the following January.

Your delay payments lifeline may be a helpful cash-management strategy, and there is certainly nothing wrong with holding your money a month longer. In the same way, it is completely appropriate for a company to take longer to pay back its vendors and reap the immediate cash-management benefits. However, just like you, companies cannot continue to delay payments into eternity.

Accounts payable is a relatively straightforward account. If you see a discussion of accounts payable that is longer than a couple of sentences, there is probably something in there that you want to know (for example, accounts payable financing arrangements).

2. Boosting CFFO by Collecting from Customers More Quickly

Another way in which companies can generate a nonrecurring CFFO boost would be to convince customers to pay them more quickly. This certainly would not be considered a bad thing, and it may even speak well of a company’s significant leverage over its customers. However, as in our discussion about stretching out payables, companies cannot continue to collect at a faster and faster rate every quarter in perpetuity. As a result, the growth in CFFO that results from accelerated collections should be deemed unsustainable.

While many investors are pleased when management says that it is “aggressively managing working capital,” you should take this as a warning sign that recent CFFO growth may not be sustainable.

3. Boosting CFFO by Purchasing Less Inventory

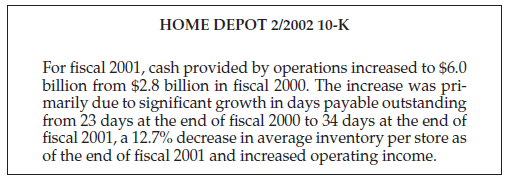

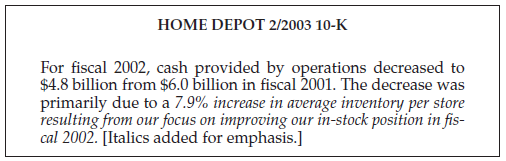

Home Depot received an unsustainable CFFO boost in 2001 from stretching out payments to vendors and purchasing less inventory. Bob Nardelli doubled Home Depot’s operating cash flow in his first year on the job by stretching out vendor payables and reducing the amount of inventory at each store. Home Depot lowered its inventory levels simply by not restocking shelves after goods had been sold. In other words, the company just did not purchase as much inventory from vendors as in previous years.

Home Depot, stretching out vendor payments produced a large positive “swing” on the Statement of Cash Flows. In the same way, failing to restock inventory levels would also provide an unsustainable boost to CFFO.

To be fair, Home Depot was very clear in its disclosure under the “Liquidity and Capital Resources” section of its 10-K filing, stating that CFFO growth primarily had been driven by an extension of payables and a decrease in inventory per store.

Buried in the 10-Qs and 10-Ks is some extra insight about the drivers of cash flow. It is one of the most important sections of the filing, but many investors don’t know it exists. To find it, turn to the Management Discussion & Analysis (MD&A)—near the back is a section often called “Liquidity and Capital Resources.” This section is a “must-read” for every company you analyse.

4. Boosting CFFO with One-Time Benefits

Microsoft Corp. doled out billions of dollars to settle antitrust litigation in recent years. One of the largest recipients, Sun Microsystems, pocketed nearly $2 billion from Microsoft in 2004 ($1.6 billion of which was immediately recognized as income). Sun presented this large one-time item in plain view on its Statement of Income, listing it separately as “settlement income.” Sun’s disclosure made it very easy for investors to understand that the income from this settlement was nonrecurring and unrelated to its normal operations; it was reported “below the line” as nonoperating income.

Sun’s Statement of Cash Flows, however, was less clear. The company recorded the $2 billion in cash as an Operating inflow (as is appropriate under the indirect method), but it was not listed separately on the SCF; rather, it was simply bundled with net income. As you would imagine, a $2 billion settlement was quite material to Sun’s results—CFFO for all of 2004 was $2.2 billion, up from $1.0 billion in 2003. Diligent investors would have noticed this settlement reflected on the Statement of Income and should have immediately realized that it was an unsustainable source of CFFO.

Nonrecurring boosts to CFFO are often not plainly disclosed on the Statement of Cash Flows. Whenever you spot any kind of one-time earnings benefit, ask yourself: “How does this boost affect the Statement of Cash Flows?”

In the next and the final article of the series we discuss the importance of using other “key metrics” to evaluate a company’s performance and economic health, and we expose tricks that companies could use to cloud the picture and mislead investors.

Disclaimers :

The information herein is used as per the available sources of bseindia.com, company’s annual reports & other public database sources. Alpha Invesco is not responsible for any discrepancy in the above mentioned data. Investors should seek advice of their independent financial advisor prior to taking any investment decision based on this report or for any necessary explanation of its contents

Future estimates mentioned herein are personal opinions & views of the author. For queries / grievances – support@alphainvesco.com or call our support desk at 020-65108952.

SEBI registration No : INA000003106

Readers are responsible for all outcomes arising of buying / selling of particular scrip / scrips mentioned here in. This report indicates opinion of the author & is not a recommendation to buy or sell securities. Alpha Invesco & its representatives do not have any vested interest in above mentioned securities at the time of this publication, and none of its directors, associates have any positions / financial interest in the securities mentioned above.

Alpha Invesco, or it’s associates are not paid or compensated at any point of time, or in last 12 months by any way from the companies mentioned in the report.

Alpha Invesco & it’s representatives do not have more than 1% of the company’s total shareholding. Company ownership of the stock : No, Served as a director / employee of the mentioned companies in the report : No. Any material conflict of interest at the time of publishing the report : No.

The views expressed in this post accurately reflect the authors personal views about any and all of the subject securities or issuers; and no part of the compensations, if any was, is or will be, directly or indirectly, related to the specific recommendation or views expressed in the report.

Stay Updated With Our Market Insights.

Our Weekly Newsletter Keeps You Updated On Sectors & Stocks That Our Research Desk Is Currently Reading & Common Sense Approach That Works In Real Investment World.